1.

The flight into Mulu National Park in Borneo is unique. You take off from Miri, are given a drinking box of Milo and 15 minutes later you find yourself landing. In that brief time you see jungle being destroyed to make palm plantations that are so big you can probably see them from space, the dense lattice of logging roads that criss-cross the forest and then the park itself.

The park sits in a valley with a few misplaced humps of mountains on one side and the towering Mount Mulu (~2,300m) on the other. If your captain is feeling excited/coming in too fast - as ours was - he may (without warning) decide to perform a corkscrew to lose both altitude and speed, thus allowing you a full view of the landscape. It's heady to see that much jungle, although it may also have had something to do with the g forces throwing you back in your seat.

2.

When you get to Mulu National Park (it's a five minute ride from the airport), the first thing that strikes you is the humidity. The rainforest is an endless cycle of water being shifted between the land and the sky. It rains 280 days a year in Mulu and each tree sheds 1,000L of water a year. This leads to the rainforest creating 75% of its own rain simply due to transpiration.

It had poured before we got here and much of the land was flooded; fortunately a raised catwalk connects everything. There was water everywhere; overnight the water dropped at least one foot and was practically gone.

Technically most parts of the park are actually swamp. You frequently find undisturbed pools of water:

Moreover, it doesn't so much rain at the park as the sky erupts. When the rain comes down you can't actually hear the drops on the tin roofs; it's more of a continuous roar.

3.

The humidity is reinforced by an eerie lack of wind. In the five days we spent in the park, there was maybe ten minutes of wind. The sky is alive with constantly shifting clouds, but on the ground there's nothing but stillness. Flags hang, the trees don't move and your clothes almost never dry.

4.

Once you get past the humidity, you're struck by the green of the place. It's as though the world was created with the most subdued colour palette of all time. At night, the sky doesn't fall, insomuch as the green is gradually replaced by black; it's like the remaining colour is sucked out of the forest.

5.

After the green, you begin to notice the height, particularly if you take a canopy walk, which affords you the jungle from the opposite perspective. It's the only way to really get a sense of the volume of flora surrounding you.

6.

The forest is a great example of how fabulously complex systems can arise out of simple rules. Since the soil beneath the jungle is so crummy - and below it is just stone - , the plants in the forest must get all their energy from the sky. From this simple constraint, the jungle has evolved many solutions.

Trees have roots that branch fractally (and sometimes grow back together) to buttress support.

Liana have developed the ultimate redundancy. They grow up into the canopy, then across and back down. Eventually they can interconnect with hundreds of trees so that they are never dependent upon one node:

And anywhere possible, plants piggyback off the trees to get to thy sky:

7.

There is a bit of colour, you just have to look for it. It's hidden below leaves, around corners and in nooks and crannies.

8.

There are a lot of bugs, and they come in all shapes and sizes. You could have a field day developing your own personal classification system based upon colour or size or shape or whatever dimension you want.

Life in the rainforest is nasty, brutish and short, so many are camouflaged to better catch prey/avoid being eaten, brightly coloured to warn away potential predators or hiding where they won't be seen.

Almost all of them will be missed unless your guide decides to point them out to you.

9.

The ants are the janitors of the rainforest and they are constantly at work. There are giant ants and tiny ants you can barely see. Red, black and black & red; some with wings; some without.

Their pathways - including some that are covered - litter the jungle. You'll see them traveling in great packs and sometimes you see them all working together to bring a treat home. We watched as twenty ants, some five of them chained together with two more pushing from behind, carried a dead bug back to their hill:

10.

Occasionally, you'll see a flash of iridescent blue out of the corner of your eye. It's not the first sign of a stroke, rather it's the flitting wings of one of the dragonflies. I literally thought I was going crazy the first time the light flashed in my eyes.

11.

An unexpected pleasure is that butterflies (and sometimes moths) of all colours constantly cross your path. There are tiny little yellow ones that travel in packs of up to 30:

Elsewhere you might find a large white butterfly with black polka dots slowing gliding towards you. Or perhaps you'll see the red ones or the black ones with red bodies and shining blue stripes. Or the ones with grey downward facing wings hiding blue top facing wings. Or the black butterflies with white polka dots. The variations are endless.

12.

Since there are so many humans around, there are few animals. However, there are a few birds (including hornbills) and the odd pygmy squirrel. What would be a pest in North America becomes a treat to see over here (seen in profile in following photo). These squirrels are also great jumpers; we watched one teach its children how to jump about ten times the length of their body (and yes, pigmy pygmy squirrels are incredibly cute).

If you're lucky you'll also come across a snake:

Undoubtedly you'll see many salamanders (particularly around dinner):

13.

I lied when I said there were few animals. There are very few animals besides bats. There are over four million bats in the park and you can find them everywhere.

Nestled in a leaf:

Hanging beside the trail:

But mostly they're found in Deer Cave where they stream out by the millions at sunset every night (unless it's raining). There are twelve species of bat in the cave and each sticks to its own. The fly out in separate groups (and not just twelve groups), forming ornate patterns as they leave.

The bats move up, down, left, right, forward and backward, but from the ground you perceive it as being projected onto the flat sky. This means that the bat groups appear to change shape like a slinky as it rockets forward. Pockets appear and then are immediately filled; the group veers one way and then momentarily back.

Some groups are only a few hundred and last a few seconds; the longest group we saw took a full six minutes to exit the cave.

Here's a video:

The reason the bats group together is to avoid being eaten by eagles. If an eagle is nearby, they will frequently form a ring in order to make it more difficult for any individual bat to be eaten. These bat-based Cheerios then meander across the sky:

14.

The bats themselves live in the many caves in the park. The mountains are made of limestone and they've gradually eroded to form a spectacular set of caves. There are over 300km of caves and they're still being explored.

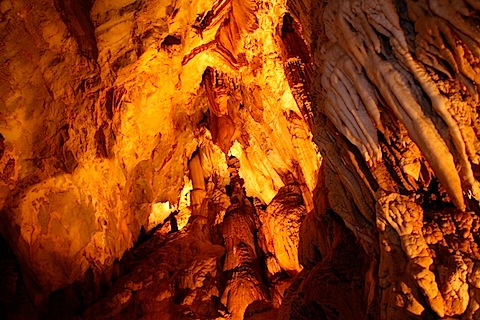

Deer cave is home to the most bats and it consequently smells like a violently abused, permanently unwashed toilet. Once you get used to this, it's actually a beautiful thing to take in:

Stay on the elevated trail, as between those rocks is an ocean of cockroach-covered guano.

At the end is a spectacular opening that looks onto the "Garden of Eden":

The scene is one of impossible beauty - and also impossible to properly photo.

You're on a hunk of rock in a giant cave as wide as it is tall looking out towards the lush jungle. The jungle is trying to invade the cave and only the lack of sun holds it back; it bleeds a river into the cave. From the ceiling, at least three miniature waterfalls have formed from water falling hundreds of feet from the ceiling; the water is so sediment rich that it's formed its own spigot for each waterfall.

Further into the park is Clearwater cave, which actually has a river running through it.

To give you an idea of scale in the above photo, there are actually people at the end of that shaft of light. They're barely visible in this photo.

15.

The other major geographic feature of the park are the pinnacles. These are a series of craggy, sharp limestone formations. They were created when the park's limestone came to the surface, cracked and filled in with soil which then washed away (and the process took millions of years).

You climb a trail that's only 2.4km long - but includes a staggering 1.2km elevation gain and you're there:

The trail up and down is treacherous. It's all wet roots, spiky limestone and there's not a single flat part. At the top you pass through a mossy forest and it becomes near vertical. There are over 15 ladders and countless ropes. At times you find your self stepping on the spikes of pinnacles to get ahead; you check your footing and pray you don't fall.

Here's a shot of what one part of the trail looks like. Needless to say, it's basically invisible:

16.

While the trail might be miserable (the pinnacles are worth it though), getting there is a blast. You stay at a camp that's in a valley between mist-covered mountains:

You can't see it in the above photo, but there are actually another set of pinnacles at the top of those limestone cliffs. Our guides told us that they have never been explored. It's hard to imagine, but here in Borneo there are actually spectacular geological features that have never been visited by anyone (I see a National Geographic special looming in the future).

To get to the camp you take a longboat up a jungle river:

It's a great ride.

17.

On the ride up to the camp, you stop off at a Penan village. The Penan are the former nomadic hill dwellers of Sarawak. There are 10,000 of them, but their forest forefathers carrying blowpipes have been replaced by tourists clutching cameras; only 300 still live in the Jungle. (For a great overview of these people, read the remarkable Stranger in the Forest)

Their language gives you a sense of just how they lived. They had words for every forest plant and creature but no word for the forest itself as they could not imagine anything but it. Similarly, "thank you" and "goodbye" were not found in their language as they were nomads who constantly saw each other again and shared everything.

Their society was extremely communal and there were over six words for describing different levels of consensus amongst groups (i.e., "we"). In fact, they're challenged to speak other languages as "we" for them is not simply the 3rd person plural and they lack our cultural context to explain the concept.

Their society was also shockingly peaceful. There is no record of a war ever occurring and there was no word for thief.

Unfortunately, the modernization of Malaysia has not been kind to the Penan. Many now live in dog-filled villages like this one:

The government is training them how to grow rice (which can't be a great future). Some sell trinkets to tourists, but few buy anything beyond the odd European picking up a blowpipe. Thankfully, a few are employed by the rapidly growing park.

18.

In closing, you should go to Gulung Mulu National Park. But go soon. Since 2005 (when it got a world heritage designation), tourism has exploded. It's now constantly booked and they're adding more facilities to a park that's already at capacity. Get there as soon as you can and be sure to book ahead; you won't regret it.