1.

We've spend the last few days skulking eastwards from Rajasthan towards Delhi. This has given us a chance to see all sorts of little towns that most people won't see as they don't have enough time. This is one of the little joys of India: the density of history is so high that there are literally hundreds of towns with something worth seeing. Compared to the great sights of India each is unremarkable, but most countries would kill to have just a couple of towns like them.

We spent a few days in Bharatpur. It initially appeared as a charmless, dusty city but in the middle of it is a massive fort. The moat now swells with plastic bottles instead of water. Once you make it past the ramparts though, things start to change.

It's a "working" castle: many people live inside the grounds plus there are the remains of various different palaces. Impressively, there's a park within the walls; this might not sound like much, but it's quite the luxury for India. Getting a fresh pomegranate juice and sitting in the park was a welcome moment.

The highlight is one of the palaces that has an ancient hammam (Turkish bath) attached:

The main reason people come to Bharatpur is to go to Keloadeo National Park. About 150 years ago the Maharajah decided that he wanted a private duck hunting area. He irrigated a 29 square kilometer plot of land and then would invite people over to slaughter animals with extreme prejudice. The British took him up in earnest; on one particularly bloody day, 39 men managed to kill over 4,000 birds (there's a plaque to memorialize these brutal hunts).

Fortunately, it's been a national park for over forty years now so there's no more hunting. You can while away a pleasant day by renting bikes and exploring the park on your own. We say a wealth of wildlife: black ibises, painted storks (below), kingfishers, peacocks, cormorants, parrots, hare, giant squirrel and the ubiquitous cow (there's not supposed to graze in the park, but hey, you know...).

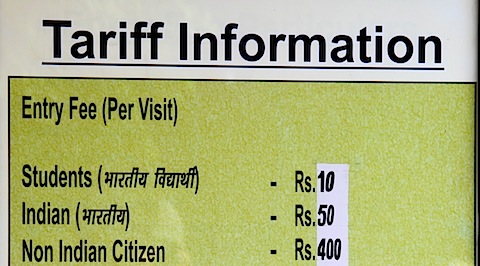

Conveniently, the folks at Keoladeo had jacked their prices - presumably for the Commonwealth Games. The price increase was so sudden that they didn't even have a chance to update their flyers, which still had the 50% lower price:

About 40 kilometers away from Bharatpur is Deeg, which is famous for its water palace. This massive complex has over 200 fountains (alas, not turned on) and many of the building still contain the original furniture (alas, photography is not allowed).

The entire place is a celebration of India's scarcest resource. Check out the maze created below for catching rainwater:

2.

India is a case study in social norms - because when you get here, you realize that so many of the things you take for granted are completely different here. To wit:

- Spitting. Every morning the men compete with one another to see who has the greatest lung capacity and can summon forth the largest loogie. This is particularly charming when you're lying in your hotel bed and all you can hear is the sound of nearby hawking.

- Littering. Almost everyone throws their garbage in the street. If you pay attention you'll notice the various different ways people dispose of their garbage: carefully pouring it on the curb for a cow to eat, tossing it off the roof or maybe just freely flinging it out the window. If, like me, you're unlucky, someone will throw their garbage out a bus window at the exact moment you're passing by in an open-aired tuk tuk.

- Dress. Shorts are vulgar and a sign of disrespect, particularly if worn in a religious building. However, it is nothing to wear a sari that exposes one's sagging stomach.

- Pedestrian rights. In a nutshell, they don't exist. People will drive right up into you and if you don't get out of the way you will be hit. If you're going to cross the road, you're taking your life into your own hands: don't expect anyone to try and dodge you. Caveat pedestor.

- Personal space. Like pedestrian rights, this is non-existent. In an overpopulated country this shouldn't be unexpected, but it takes a while to get used to people coming right up to you. More awkward is when you're riding on the bus and the unperfumed man in the seat next to you puts his arm behind you and rotates toward you, allowing his ample stomach to sag over your leg. Did I mention that I hate being touched by people I don't know?

- Personal space II. Indians love music and associate it with a good time. Consequently, people play music here all the time (see Agra below). For most people this means on their cellphone. However, nobody uses headphones: they just blare their music without consideration of what anyone else. Manufacturers have caught on: the #1 feature in an ad for a popular phone is its dual stereo speakers.

- Queueing: forget it, it's a battle. Everyone for themselves. Sharp elbows are mandatory or you'll still be standing in line an hour later.

Now, these are social norms and that means that they're learned behaviour and changeable. The Indian government seems to think that a few of them might be worth trying to change: there are ads on tv to teach people that cutting in the line is bad behaviour and that some civility in driving can be nice. Moreover, in the few areas of the country that have garbage cans (e.g., Amber Fort, parts of Agra) you will see nary a piece of litter.

It will be interesting to see which ones society chooses to keep vs. change.

3.

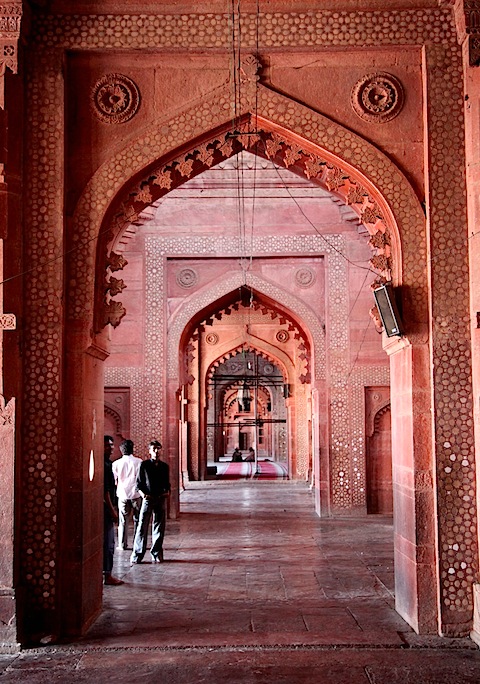

After Bharatpur we went to Fatahpur Sikri. This tout-filled town used to be the capital of the great ruler Akbar, but it lacks a steady supply of water and was abandoned after Akbar's death. It's now a UNESCO world heritage site with an impressive mosque and equally incredible palace.

The only thing more 'impressive' than the buildings is the tenacity of the touts. We arrived via a motorized rickshaw; touts actually jumped into the front seat where our driver was sitting (people are always hopping on/off the front of your rickshaw, hence this was nothing new) and persuaded him to drop us off far from our hotel. I fell for this, forgetting the basic rule of travel: never get out of the vehicle before your destination, and thus had to deal with the touts.

This was not my finest moment. I was soon swarmed by at least 8 guys all trying to sell me postcards, multiple rickshaw rides, trinkets, bangles, guides, hotel rooms, etc. And nobody would take no for an answer. After trying to walk away and telling everybody "no" at least three times, I lost it. I quickly became that guy I never wanted to be and found myself screaming expletives at the touts to get them to go away. LIke I've said many times in this blog, traveling in India can be hard.

After we checked into our hotel we went to Akbar's great mosque, graced by the mighty 54 meter tall Buland Darwaza (Victory Gate).

The touts have taken over this mosque complex - I think mainly because it does not charge an entrance fee. You have to leave your shoes outside where, if you're a foreigner, you'll have to pay a kid for the privilege of not having them stolen. Once inside, a tout - who insists that he is not a guide and will not, under any circumstances, accept payment - guides you around the complex; you have no choice but to accept. As you marvel at the architectural details and finery of the mosque and adjoining buildings, you'll also get to fend off his attempts to sell you blankets, soapstone carvings and the eventual negotiation of a 'gift' for his services (and all the while he will tell you that you're being rude/cheap by not buying anything/giving him more money).

Fortunately, next door is Akbar's tout-free palace complex. Akbar is one of history's most fascinating rules: while a muslim, he had three wives - one Christian, one Hindu and one Muslim. He understood that it was much more efficient to subdue the Hindu population by negotiation than force and his reign was marked by prosperity and growth. This is evident from the remarkable complex he left:

One of the most interesting buildings is the Diwan-i-Khas (Hall of Private Audiences) where Akbar would speak with is advisors. He stood on an upraised plinth, each connected by a gangway to a corner where a minister would stand. He would ask a question and rotate through his advisors for answers:

4.

There's not a heck of a lot to do in rural India at night, so when we've tired of reading, we've watched tv. Indian television is a 200 channel universe of soap operas, Bollywood movies, singing, dancing, Business Television (talking heads and scrolling headlines who take themselves very seriously), holy men and the odd foreign channel.

You start to realize that there are certain archetypes in the tv culture:

- The man-child: an early twenties to mid-thirties male who wears jeans and frequently a wife beater (known here in its less pejorative term, the "sleeveless vest"). He is truculent and insolent and incredibly cool yet still able to respect his elders.

- The urban modern: an early- to late-twenties woman who wears western clothes, works, and lives in an apartment in a major city. She represents all of India's hopes for the future yet secretly also their fear that modernizing may require them to sell out their culture

- The self-confident traditionalist: also an early- to late-twenties woman who only wears saris and traditional clothes. She is much more reserved and subdued than her urban modern counterpart, but do not try and run truck over her. She embodies an India unsure of what it wants, trying to balance all of the nation's history and traditions amongst the technology and pace of the modern world

- The dominator: mid-forties to mid-sixties men and women who play overbearing father - and more usually - mother-in-laws. Again, this is the best and worst of India. They hold the family together and ensure that traditions and heritage are passed from generation to generation. Simultaneously, they do not easily let their children grow free and learn to live for themselves.

You may notice that there are a couple of groups that aren't too well represented here:

- Kids: you only see them in commercials

- Seniors: as far as tv is concerned, they might as well not exist

- Women with kids: ditto. You should be at home raising your kids, not being on tv. Only men of this age should be on tv.

Equally interesting are the breadth of commercials (I subscribe that the best way to get a feel for what a society feels about itself is to watch its television commercials). Almost all are deludedly aspirational: people sip coffee or eat snacks in beautiful, modern apartments that look like they're out of New York or London. Some are ridiculously macho: a beautiful woman in an evening gown signals with a handkerchief, causing a jeep to burst over a sand dune; a man gets out with a golf club and knocks a ball into a cup. And many play to your emotions by using children as pawns; perhaps that why you otherwise don't see many on tv.

A couple of the more interesting commercials we saw were related to matrimony. Most marriages here are arranged (a Western style marriage is called a "love marriage") and it's near impossible for guys to meet girls. One ad we saw was for a matrimony service; think online dating where the goal from the outset is finding a wife.

Another ad started with a stunning woman staring at the camera stating unhappily and stating: "ours was an arranged marriage". Cut to various scenes of her and her husband feigning interest for one another while obviously masking an inner indifference. However, then one day on the train they try to find each other and realize that they actually love one another! And then they go out and buy matching rings to celebrate the day they fell in love after they were already married.

Probably the strangest thing on Indian television are the channels devoted to various gurus and religious leaders. These channels are pretty basic: a guy sits on a stage and yells/dictates/sings while an audience watches or calls in. This is a very conservative society so there's no boobs or bad words on tv, but occasionally something odd slips in via these channels. We were flipping channels and witnessed a ceremony where an overweight, naked, middle-aged guru walked up to a row of seated disciples and touched each of them on the head. These brave pilgrims sat unblinking.

Like I said, tv is a fascinating window into a country.

5.

What is that noise? Is someone throwing squirrels in a meat grinder? Has a hyena been run over by a steam roller? Oh no, it's just 5:30 in the morning in Agra and the local sound system (they're everywhere in some towns) has decided to crank some Hindi music at 150% of tempo.

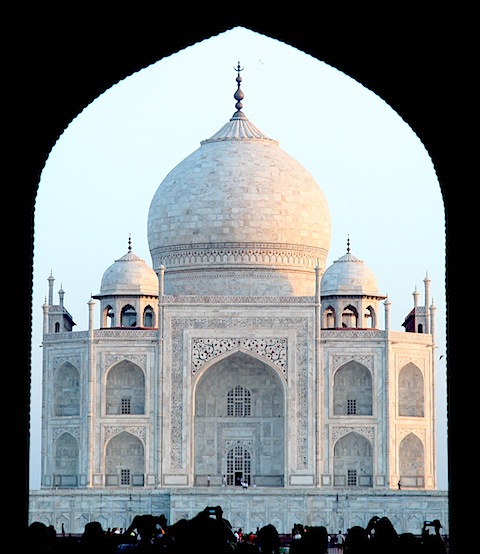

Well, sleep is blown, so let's get up and go see the Taj Mahal.

But before the Taj, let me tell you about a couple of other stunning attractions that Agra has.

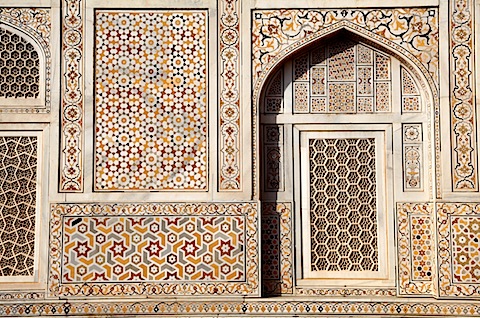

If it were in another city, the Itmad-Ud-Daulah, aka The Baby Taj, would stand on its own as a powerful tourist attraction. Due to the Taj, it gets barely any traffic. Which is a shame, as most people will miss out on the incredible detail that has gone into its construction (like the Taj, it too is a mausoleum to a lost wife):

Agra Fort is another of India's innumerable UNESCO world heritage site (no other nation has done as good a job of getting their monuments listed as India; it seems like there's one in every city - and each is legitimately on the list). This massive fort is steeped in the complex political history of India. Aurangzeb's father built the Taj Mahal; he overthrew his father and locked him up for the rest of his life (8 years) in a room that overlooked the Taj; Aurangazeb's throne overlooked both his father and the Taj.

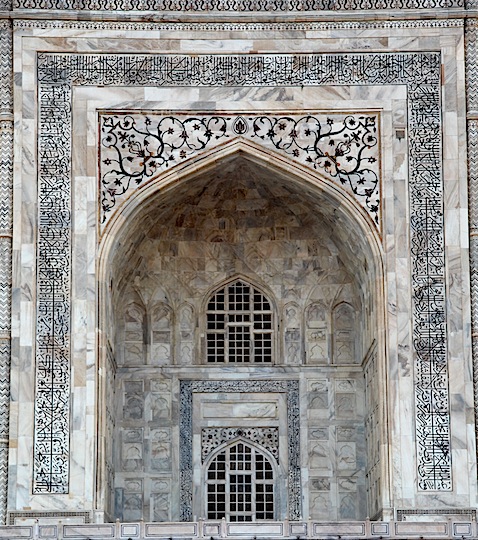

Despite their individual grandeur, each of these sites is overshadowed by the Taj Mahal. Simply put, the Taj is just that much more amazing that just about any other building you're seen. Viewed in the morning sun at a distance of 200 meters or so, it radiates like the perfect embodiment of one man's love for his lost wife. As you get closer the immensity is replaced by the ornate detail and the subtlety of the carvings combined with marble so polished that it reflects.

It would be criminal to visit Delhi and not go to the Taj.

6.

Speaking of which, as we drove into Delhi everything began to make a little bit of sense.

As we've been traveling through this country, one the biggest mystery to me has been "what does everyone here do for work?" This has been made even more puzzling for two reasons:

- As we've driven through dozens of towns - some with populations in the millions - we've hardly seen any factories. Contrast this to the Factory To The World that is Southeast Asia/China where the social contract is obvious: move to a town, work in factory, remit money home and live a better life than your parents

- We see ads everywhere - and I mean literally everywhere: in magazines, on billboards, painted on walls - for IT, engineering and management education. My favourite ad showed two young women in leggings sitting at their laptops happily working away; nothing could have been a better embodiment of what this country oh so yearns to be. However, all of these factory-less towns have also been IT-less towns; no squat, shiny, campus-style mirrored buildings that smell of technology companies

This has compounded the disbelief I've had watching television here; especially when watching commercials, I haven't been able to figure out where in India it's supposed to be. The apartments? People in parks? Most of the scenes look as foreign from where I've been as Mars. Now I know that Indians have a great suspension of disbelief - witness your average Bollywood movie; sheer escapism - but this was bordering on the delusional.

But back to Delhi, as it all started to come together.

As you drive into town, you immediately notice how different it is. On the outskirts, brand new technical universities (Fully air-conditioned! 100% placement assistance!) are emerging out of the dusty plains. The tentacles of a metro (infrastructure!) reach into the hinterlands and tower over many city neighbourhoods.

The metro has brought with it easy transportation and alongside it sprout multi-storey shopping malls, giant apartment complexes and corporate offices. Those fancy, glass-enclosed, three storey testaments to technology that India so covets as its hope to becoming a superpower.

Bingo. Now this country is starting to make sense! Now I have an inkling of how it works and what it might mean.

So, what do I think? Well, I think that in India we're witnessing the eradication of poverty and the rise of a middle class on a pretty massive scale. I also don't think it's happening anywhere near fast enough - and particularly not fast enough for India to become a major superpower any time in the next twenty years.

The crux of this is due to India's focus on services and allowing China to have all the manufacturing fun. Services, on a per person level, probably bring in more income per job than manufacturing. But it comes at a cost: you need a highly trained workforce. That education is not going to come from the government alone (a high school diploma ain't enough), so India has been building out a massive higher educational infrastructure.

However, it takes a heck of a lot longer to build a university and get it up to speed than it does to build a factory to assemble irons or lampshades. So you can't grow as fast as your neighbour to the north. It also means that you've got a small part of your workforce (the service sector) fully employed and the vast majority of your workforce (the other 90+% of your workforce) vastly underemployed.

There's a more subtle - and potentially more socially jarring - long-term consequence to this as well. People who work in services are going to want to work almost exclusively in big cities. Intellectually stimulating work tends to require intellectually stimulating play in your spare time and alas that's typically not found in villages (for more, read Richard Florida or John Hagel). Moreover, these people are going to move to cities where there are already people like them; they're less likely to slug it out in a 'boring' city (unless the pay is really, really good; not a likely prospect right now).

I think this explains why so many of India's highly educated elites go abroad for work and show little interest in returning. It's not that they're not Indian patriots, rather they're too stimulated by what they get overseas and can't imagine going back until something similar arises in India. And once they have kids, they almost certainly won't go back as their kids won't give up what they've got.

But something similar is arising. I believe that India is going to see the rapid rise of a few incredible cities that will be more like states. They'll go toe-to-toe in attracting the best and brightest across the world. Think Delhi, Mumbai, Chennai and Bangalore. Maybe not for a few more years, but barring catastrophic mismanagement (which is a possibility due to the endemic corruption here), they'll get there.

The flip side of this is that this means huge wealth disparity in the country. India's elites will be more comfortable and able to better to relate to people in London, New York and Tokyo than people in a rural village in Uttar Pradesh or Bihar. In ten years I wouldn't be surprised to see something like 250,000 dollar millionaires (currently about 115,000) and 400 million people living on less than $2 a day. The wealth inequality is going to make America look like a socialist country.

Is this bad for India? I honestly don't know. It might not happen; if it happens and is left unchecked it could lead to ridiculous scenarios like secession demands by the new princely city states who want to be the new Dubai (I'm being purposely melodramatic).

It's also definitely not irreversible. India currently has zero focus on reducing poverty in the country at either the personal or governmental level (literally: the rich don't give to charity and there's no national strategy or execution on improving welfare). If this changes to spread the wealth around - and this doesn't mean higher taxes; it likely means better thought growth policies - the situation could definitely change.

It's going to be really interesting to see how this country plays the hands it's been dealt. Mixing metaphors, the ball's in your court India!