Today at work we were fortunate enough to have Mark Hurst come in and talk about his updated book Customers Included. It's all about working backwards from customers' needs - which is a pretty easy sell in Amazonland (see "Customer Obsession") - and hence recommended reading.

What I most enjoyed about his talk was his thorough destruction of the pernicious "Steve Jobs didn't listen to customers so I don't need to" myth. Few things in life are as soul-crushing as hearing someone (usually someone who has never created anything) tell you all about how they don't need to listen to customers because Steve Jobs didn't.

Any person who has spent any time trying to create new products knows in their bones that if you're going to be successful, you've got to have some key insight as to what customers want - and the most successful way of doing that is working backwards from a customer need.

If the greatest trick the devil ever pulled was convincing the world that he didn't exist, then Steve Jobs' Kaiser Soze impression was convincing folks that he didn't listen to customers. Fortunately, Mark Hurst is here to help us dive deep and discover the truth.

Article #1 - The 1997 WWDC

1997 was not a great year to work at Apple. They were almost out of money and turned to Steve as the only guy who could (or would) save the company. At the 1997 WWDC he did a fireside chat with Mac developers - who are the most invested people in the entire Mac ecosystem. It's their livelihood and they're the most diehard converts. So, it was probably a bit of a surprise when this question got asked:

https://youtu.be/6iACK-LNnzM?t=3026

Here's the lightly edited transcript for you:

Questioner: Mr Jobs, you're a bright and influential man. It is sad and clear that on several counts you've discussed you don't know what you're talking about... And when you're finished with that, perhaps you can tell us what you have personally been doing for the last seven years.

If you're watching the video, you'll notice a quick joke as a response followed by a long, awkward pause as Steve tries to think of the following capable response:

One of the hardest thing when you're trying to effect change is that people, like this gentleman are right, in certain areas. ...The hardest thing, what does that fit in, to a cohesive, larger vision that's going to enable you to sell eight billion, ten billion dollars of product a year. One of the things I've always found is that you've got to start with the customer experience and work backwards to the technology. You can't start with the technology and figure out where you're going to sell it. And I've made this mistake probably more than anybody else in the room. And I've got the scar tissue to prove it and I know that it's the case. And as we've tried to come up with a strategy and a vision for Apple, um, it started with what incredible benefits can we give to the customer. Where can we take the customer. Not starting with, let's sit down with the engineers and figure out what awesome technology we have and how are we going to market it. And I think that's the right path to take.

There you have it: the greatest tech legend of recent years talking about working backwards.

Article 2: The Creation of the iPhone

So Jobs said he worked backwards, but how did he do that when creating products that never existed before? Well, the iPhone came about by working backwards from the compromises made by consumers in using existing (circa 2005) cellphones.

From the Walter Isaacson biography (page 466):

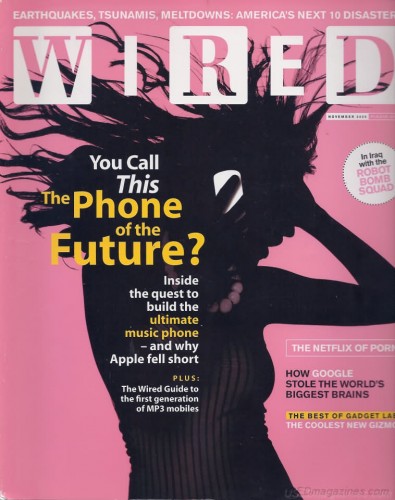

He [Jobs] began talking to Ed Zander, the new CEO of Motorola, about making a companion to Motorola's popular RAZR, which was a cellphone and digital camera, that would have the iPhone built in. Thus was born the ROKR. It ended up having neither the minimalism of the iPod nor the convenient slimness of a RAZR. Ugly, difficult to load, and with an arbitrary hundred-song limit, it had all the hallmarks of a product that had been negotiated by a committee which was counter to the way Jobs liked to work. Instead of hardware, software, and content all being controlled by one company, they were cobbled together by Motorola, Apple, and the wireless carrier Cingular. "You call this the phone of the future?" Wired scoffed on its November 2005 cover.

The next paragraph gets to the interesting part:

Jobs was furious. "I'm sick of dealing with these stupid companies like Motorola," he told Tony Fadell and others at one of the iPod product review meetings. "Let's do it ourselves." He had noticed something odd about the cell phones on the market: They all stank, just like portable music players used to. "We would sit around talking about how much we hated our phones," he recalled. "They were way too complicated. They had features nobody could figure out, including the address book. It was just Byzantine." George Riley, an outside lawyer for Apple, remembers sitting at meetings to go over legal issues, and Jobs would get bored, grab Riley's mobile phone, and start pointing out all the ways it was "brain-dead." So Jobs and his team became excited about the prospect of building a phone that they would want to use.

This is classic working backwards from the customer. Identify all the compromises faced by the customer. Heck, test your hypotheses with your target market (rich lawyers with lots of disposable income for phones) before you build anything. But don't pretend that this was just willed out of thin air.

Hurst called out one important corollary to the above: when deciding what the compromises are, there's no mention of "multi touch" or "gorilla glass," etc. All those fancy design features came later once the team had identified the customer problems. They were the "how" to solve the "what" which was crappy address books, etc.

Thanks Mark for a thorough debunking of one of Silicon Valley's most pernicious, lasting myths.