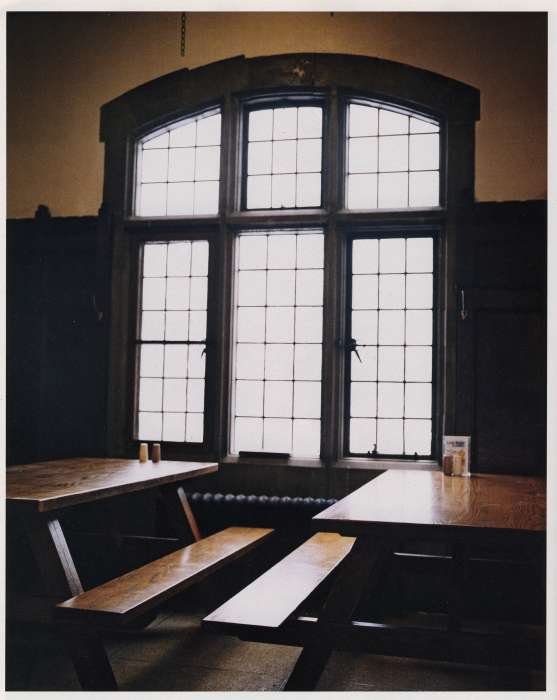

Over the past few days I’ve been reading through a stack of Wired magazines that have accumulated in my apartment over the past few months. As I was reading through an article Eureka! (a photo essay on where inspiration comes from), I came across the following image:

It’s the Cornell cafeteria where in 1946 Richard Feynman watched some students spin plates in the air. Improbably, these plates would lead to a Nobel Prize:

Within a week I was in the cafeteria and some guy, fooling around, throws a plate in the air. As the plate went up in the air, I saw it wobble, and I noticed the red medallion of Cornell on the plate going around. It was pretty obvious to me that the medallion went around faster than the wobbling.

I had nothing to do, so I start to figure out the motion of the rotating plate. I discover that when the angle is very slight, the medallion rotates twice as fast as the wobble rate — two to one. It came out of a complicated equation! Then I thought, “Is there some way I can see in a more fundamental way, by looking at the forces or the dynamics, why it’s two to one?”

I don’t remember how I did it, but I ultimately worked out what the motion of the mass particles is, and how all the accelerations balance to make it come out two to one.

I still remember going to Hans Bethe [1967 physics Nobel Laureate twelve years Feynman’s senior] and saying, “Hay, Hans! I noticed something interesting. Here the plate goes around so and the reason it’s two to one is …” and I showed him the accelerations.

He says, “Feynman, that’s pretty interesting, but what’s the importance of it? Why are you doing it?”

“Hah!” I say. “There’s no importance whatsoever. I’m just doing it for the fun of it.” His reaction didn’t discourage me; I had made up my mind I was going to enjoy physics and do whatever I liked.

I went on to work out equations of wobbles. Then I thought about how electron orbits start to move in relativity. Then there’s the Dirac Equation [Paul Dirac, 1933 physics Nobel Laureate] in electrodynamics. And then the quantum electrodynamics. And before I knew it (it was a very short time) I was “playing” — working, really — with the same old problem that I loved so much, that I stopped working on when I went to Los Alamos: my thesis-type problems [at Princeton]; all those old-fashioned, wonderful things.

It was effortless. It was easy to play with these things. It was like uncorking a bottle: Everything flowed out effortlessly. I almost tried to resist it! There was no importance to what I was doing, but ultimately there was. The diagrams [Feynman diagrams] and the whole business that I got the Nobel Prize for came from that piddling around with the wobbling plate. (Source)

When Feynman looked back to his Nobel Prize-winning work, he wrote:

It was the first time, and only time, in my career that I knew a law of nature that nobody else knew. The other things I had done before were to take somebody else’s theory and improve the method….I thought of Dirac, who had his equation [of 1928] for a while – a new equation which told him how an electron behaved – and I had this new equation for beta decay, which wasn’t as vital as the Dirac equation, but it was good. It’s the only time I ever discovered a new law. (Source)

Why do I share this? Three reasons:

- It’s hard to have an original thought: Feynman is considered one of the greatest minds of the 20th century yet he concedes that in his entire career he only had one truly original discovery

- Since it’s so hard to have an original thought, make sure you’re having fun. It’s a long road so you’d better be enjoying the ride

- Be curious about the world – you never know where or how inspiration is going to strike